Words and Photos by

Elisha Nunez

Additional photography courtesy

EPMA

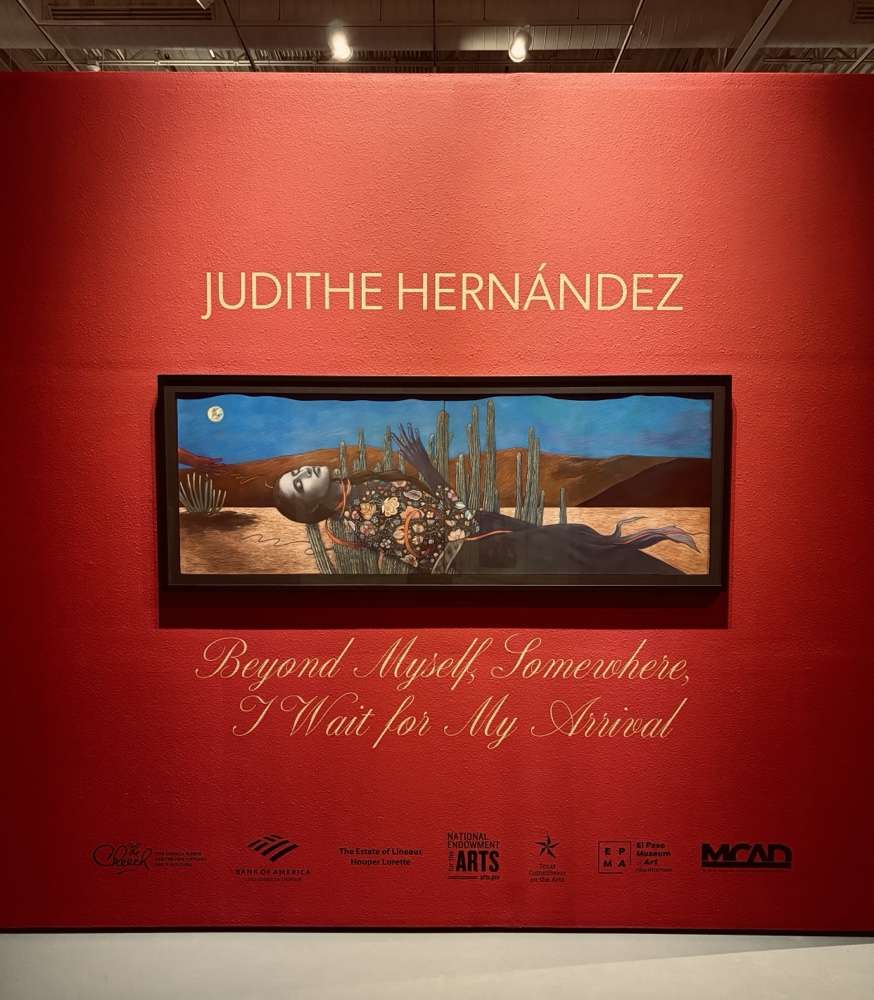

She lies still under the desert moon as her calm face gives the observer an odd sense of peace. The cactus behind her is the only thing keeping her company. She remains in her dark, torn skirt and colorful huipil, a garment worn mostly by Central and Southern Mexican women. She remains in the remnants of a promising life as a menacing red hand leaves her behind. The observer cannot help but ask, “Who is she?”

She is “La Santa Desconocida” and she greets you to the El Paso Museum of Art’s latest exhibition, “Judithe Hernandez: Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival.”

Opening on Feb. 15 at the Woody and Gayle Hunt Family Gallery the exhibition made its first debut in El Paso featuring around 80 works made by Hernandez after its time at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture.

A trailblazing Chicana artist, Hernández has roots in the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s when her artistry came to life. Based in Los Angeles, her series has challenged patriarchal norms in Hispanic culture and uplifted Chicana stories. Raised by an El Pasoan mother, Hernandez’s familiarity with the Borderland has also been shown in her artworks, like with her “Juarez” series.

When walking into the gallery you see the pastel on paper drawings of the femicides in Ciudad Juárez. Her painting “Juarez Quinceañera” shows a young girl in a black dress holding two white flowers. She wears a haunting Mayan mask as she stands in front of a pastel pink wall marked with bloody handprints.

“Juarez: Ciudad de la Muerte” shows a nude woman of greenish skin and red hair, her back facing the audience. She is seen with barbed wire strangling her neck as colorful papel picado floats above her with statements like “Feminicidios” and “500 Muertas.”

Hernández has a way of mixing indigenous and modern elements while also showing stories of women, victims of the femicides in Juarez. From folktale references to colonial traditions, Hernandez shows viewers the struggles that Chicana and Latina women encounter.

“It’s a battle of both indigenous and colonization, AKA the Mestizo identity. A lot of it depicts indigenous tribal wears, but then you have loteria cards and stuff like that. It’s heavy on symbolism, it’s heavy on folklore,” said Michael Reyes, the El Paso Museum of Art’s senior curator.

These artworks interpret different sides of the femicides like the struggles of living amid the tragedy of being a victim. That said, there are different takeaways from the series. Some may see the women as victims, but others may see them as protagonists in the forefront of a movement seeking justice for women.

“I think it’s supposed to teach individuals not only the story, but empathy. Some of them were pretty intense,” Reyes said.

“People walk away saying it’s an empowerment of resilience (and the) female spirit. The femicides were for a long time, for a whole decade. Women are still resilient and still fighting for their sisters.”

While Hernandez’s series about the femicides empowers women through surreal and almost violent depictions, her “Adam and Eve” series does so by balancing boldness with vulnerability.

In one of her works we see “The Birth of Eve” with the biblical heroine laying nude in a bed of lilypads. Her eyes are closed as she remains submerged underwater, the self-sustaining plants creating a peaceful pattern around her.

Flowers bloom near the crown of her head and a red hand seems to be leaving a bright red flower at her chest, which she holds on to.

While she appears peaceful and almost exposed, she lies in the same scenario a few feet away, but with a few differences. In “Sleeping Eve” she rests with her back to the audience.

She dons a luchadora mask with sharp antlers, showing this new side of Eve some may have never thought of. A school of koi fish circles her, symbols of strength and ambition as she lies against a bed of smooth rocks as a yellow snake curls around her.

Here, she seems different.

Gone is the vulnerable and delicate Eve many may think of when remembering the biblical figure. In this depiction, she is seen with more masculine elements. The mask she wears shows that she too has a strength of her own, one she can show others when provoked.

“I really think the bigger goal is a sense of empowerment, that a woman can be visible (and) can tell their story,” Reyes said.

“It really tells the downfall of Eve, but in the sense when you look at it, Eve is incredibly empowered in almost all the works over there.”

From tragedy to retelling, Judithe Hernández has told stories through her art that still resonate with people today. Themes of feminism are plentiful throughout her projects and are told in many different ways through incorporating different aspects of Hispanic culture.

“They’re going through a journey, they’re in some transition. They’re experiencing some pain or hubris,” said Edward Hayes, the director of EPMA.

“They’re in front of kind of a mystical landscape (and) just incredibly mysterious. (It shows) the struggle and mainly the journey of women through all these different narratives, cultural, historical.”

With events and stories that are especially relevant in a place like El Paso, the El Paso Museum of Art has brought an exhibition that can speak of the ways women can fight for themselves and each other.