By: Henry Craver

We live in a special part of the world. It’s sunny all year round, people are friendly, and the food is great–it’s Mexican food, after all. But there’s something else that’s tough to put your finger on, a unique flavor that coats experience around here. Chalk it up to the desert climate or our history–the Mexican revolution was born here–El Paso Del Norte is raw and exhilarating.

We live in a special part of the world. It’s sunny all year round, people are friendly, and the food is great–it’s Mexican food, after all. But there’s something else that’s tough to put your finger on, a unique flavor that coats experience around here. Chalk it up to the desert climate or our history–the Mexican revolution was born here–El Paso Del Norte is raw and exhilarating.

That feeling, whatever exactly it is that characterizes life in this slice of borderland, is perfectly embodied by our local spirit–sotol. Distilled from the hearts of wild-harvested desert spoon, the drink is hard and earthy, tasting like the desert air right after a much-needed rain, and has been crafted by Chihuahuan and Duranguense sotoleros for hundreds of years.

Don’t feel bad if you’ve never heard of the stuff, not many have. Sotol isn’t nearly as popular as its cousins, mezcal and tequila—tequila is actually just a variety of mezcal. Even around Juárez, only knowledgeable drinkers seem to know of it. Furthermore, of those familiar with the name, most have never actually tried it themselves. They warn that it’s extremely potent and possibly even dangerous. It’s a moonshine to them, consumed exclusively by impoverished, rural men for no other reason than to get drunk–even if it turns them blind.

According to Juan Quintero, co-owner of the Black Orchid Lounge in El Paso, that stigma has unjustly dogged sotol for close to a hundred years now. “My wife Michelle grew up in Juárez and she thought it was nasty. That’s the reputation it had and, unfortunately, still has to some degree,” he explained.

For centuries, sotol was wildly popular in the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango and Coahuila. In fact, by the turn of the 20th century, Chihuahua was producing 200,000 liters a year for its 340,000 residents–that’s over half a liter per person without even subtracting the kids. But the golden years of sotol wouldn’t last much longer. In 1920, the 18th amendment went into effect, officially kicking off the United States’ prohibition era. Of course, that didn’t stop Americans from drinking. Appalachian bootleggers switched into high gear and smugglers on both borders started crossing alcohol illegally to make sure people got their fix. One of hottest ports of entry was right here, between Juárez and El Paso. Savvy Mexican business people were quick to take advantage of the new opportunity, refashioning sotol production sites into bourbon-style whiskey distilleries–a drink more in line with tastes up north. At the behest of the new whiskey dons and a Chihuahuense elite that had never liked sotol to begin with, law enforcement began tracking down what was left of small-scale sotol producers and making them close shop.

For centuries, sotol was wildly popular in the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango and Coahuila. In fact, by the turn of the 20th century, Chihuahua was producing 200,000 liters a year for its 340,000 residents–that’s over half a liter per person without even subtracting the kids. But the golden years of sotol wouldn’t last much longer. In 1920, the 18th amendment went into effect, officially kicking off the United States’ prohibition era. Of course, that didn’t stop Americans from drinking. Appalachian bootleggers switched into high gear and smugglers on both borders started crossing alcohol illegally to make sure people got their fix. One of hottest ports of entry was right here, between Juárez and El Paso. Savvy Mexican business people were quick to take advantage of the new opportunity, refashioning sotol production sites into bourbon-style whiskey distilleries–a drink more in line with tastes up north. At the behest of the new whiskey dons and a Chihuahuense elite that had never liked sotol to begin with, law enforcement began tracking down what was left of small-scale sotol producers and making them close shop.

Sotol never completely disappeared, however. Far from the cities, maestros de sotol continued to make the spirit artisanally, just as their forefathers had done before them. Sometimes, bottles would find their way into the dive bars of Juárez and Chihuahua City, but for the most part, sotol could only be procured from the producers themselves. They sold it out of their houses, often in old two-liter Coke and Fanta bottles.

In recent years, however, sotol has started to experience a small resurgence. A short list of proud, Chihuahuan entrepreneurs have gotten behind artisanal sotoleros; branding, bottling and distributing their liquor. It’s started to gain traction in the trendiest big market cocktail bars, reported Juan, who carries five different brands at Black Orchid. “My wife and I first saw it a few years ago in New York at Please Don’t Tell, which is like one of the best bars in the country … a couple weeks ago, an Italian came in here and started ordering different sotols. Turned out he was the owner of an upscale bar in Rome and was headed to Chihuahua to do a little sotol tour.”

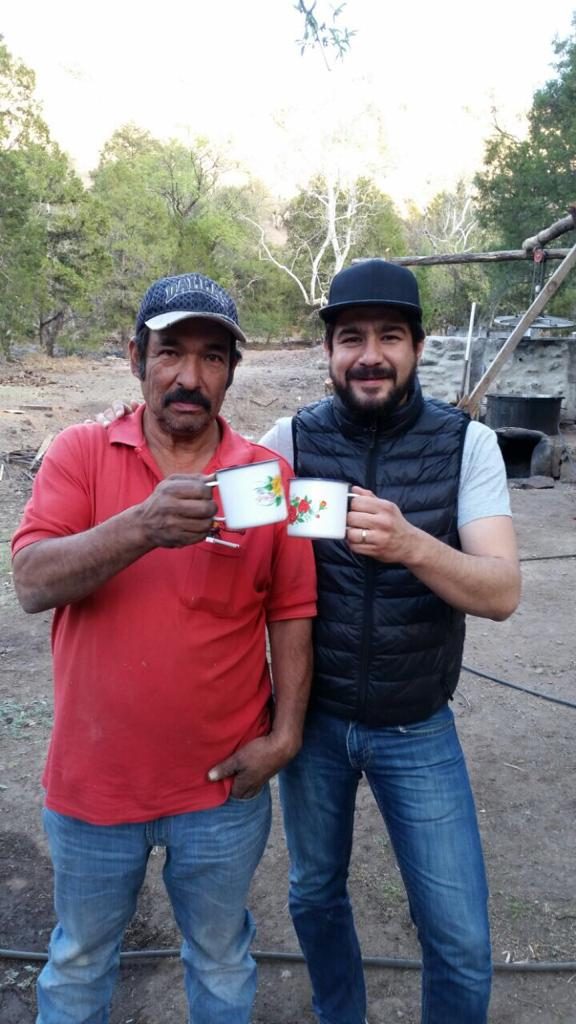

One of the figures responsible for sotol’s sudden visibility is Jesús Navar, co-founder of Flor Del Desierto Sotol. A native of Juárez now living in El Paso, Jesus started the artisanal sotol brand alongside his sister, Yaremi, around six years ago. The company currently features liquor from two producers, one located in Chihuahua’s desert plains and the other high up in the mountains. Jesus explained that a sotol’s taste differs significantly depending on where it’s made and the sotolero’s skill. He happens to think that his two solteros are some of the best around: “Don Gerardo Ruelas and Don Jose Armando Fernandez Flores both learned from their fathers, who also learned from their fathers. It’s really cool because they’re finally getting the recognition they deserve.” They’re also both finally getting the pay they deserve, he went on to explain.

Although sotol is certainly growing more popular, it’s still unclear if this is the start of a boom, similar to mezcal’s meteoric rise, or if it’s destined to remain a niche product. Ismael Gomez, who sells Flor Del Desierto in the U.S. through his Laika Spirits distributing company, doubts that it will ever reach the level of mezcal or tequila: “I think it’ll get much bigger than it is now, but I don’t ever see it getting huge. That’s not a bad thing, though. There’s a lot of stuff happening in mezcal that I really don’t like right now, quality wise and in terms of environmental sustainability.”

Although sotol is certainly growing more popular, it’s still unclear if this is the start of a boom, similar to mezcal’s meteoric rise, or if it’s destined to remain a niche product. Ismael Gomez, who sells Flor Del Desierto in the U.S. through his Laika Spirits distributing company, doubts that it will ever reach the level of mezcal or tequila: “I think it’ll get much bigger than it is now, but I don’t ever see it getting huge. That’s not a bad thing, though. There’s a lot of stuff happening in mezcal that I really don’t like right now, quality wise and in terms of environmental sustainability.”

Juan, who’s originally from Jalisco, the home of Tequila, believes sotol could be the next big thing in Mexican spirits. However, he explained, it must first be embraced by locals: “I remember growing up in Jalisco, everybody was like a little marketing machine for tequila. We were proud of it and wanted the world to know about it. That has to happen with sotol.” That local embrace is long overdue. Those interested in trying sotol should head over to Black Orchid where it’s served neat and in a number of delicious cocktails. Or, if you prefer drinking alone, you can grab a quality bottle at Juanito’s Liquor Store.

Salud.